South Africa marks the end of a remarkable judicial career

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 led to a rash of constitution-making in central and eastern Europe, as those national entities released from Soviet domination wrote the charters for their future governance. This was frequently done under American influence.

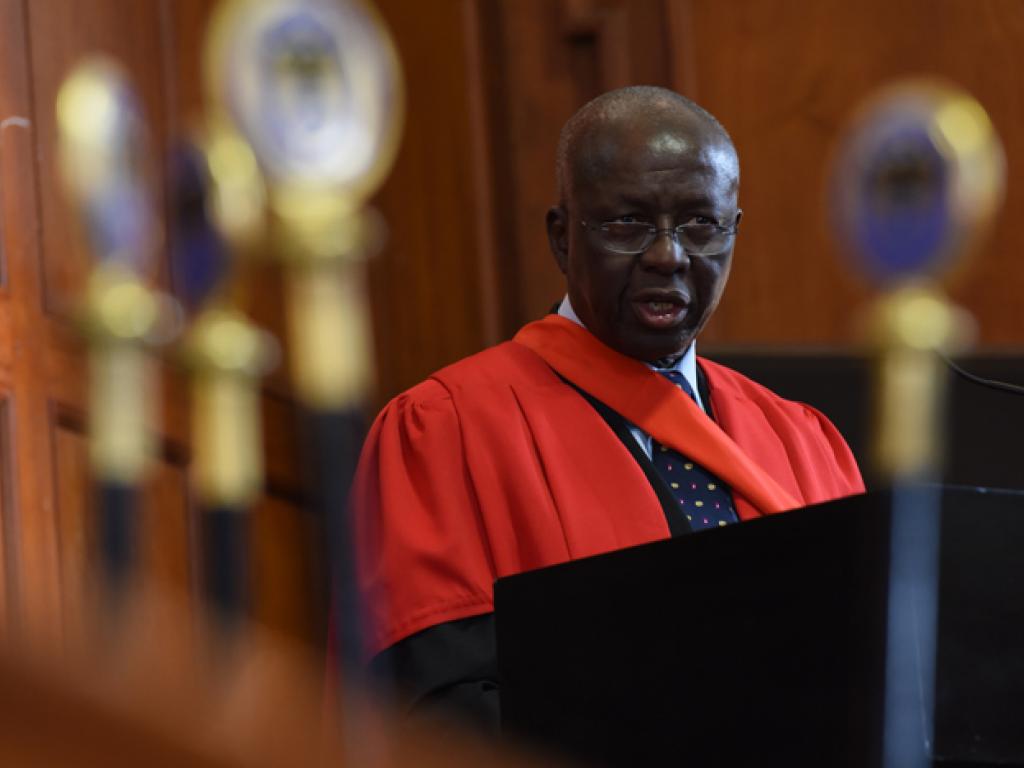

Dikgang Moseneke addressing graduates at the June graduation ceremony recently.

A similar tide of constitutional revisionism swept through Africa south of the Sahara. It was triggered by the long-brokered United Nations deal to free Namibia from South African occupation in early 1990. It was later given a great boost by the arrival of formal democracy in South Africa itself in 1994.

The adoption of the founding principle of limited government authority under law, percolated in turn through a number of countries in southern and east Africa. This took the form of a written constitution based more on the European post-war model than the American approach.

This trend had inevitable consequences for the judicial branch of government. The top court under each such constitutional system became the final arbiter of the lawfulness of the extent and manner of exercise of any government power.

The courts thus became more frequently involved in “political” decisions, with direct impact on the qualities deemed appropriate for appointment to the Bench, and the method of appointment of superior court judges. A nuanced understanding of the limits of judicial authority became essential, a quality often developed through participation in struggles for justice.

Some countries took the opportunity to create new courts or to change the membership of the most senior judiciary. South Africa chose the first approach, establishing the Constitutional Court (Concourt) in 1994, and appointing to its ranks seven members new to judicial office, and four drawn from the ranks of serving judges.

The retirement of Dikgang Moseneke, one of South Africa’s eminent judges and the Concourt’s deputy chief justice, invites a moment to reflect on the court’s place in society, and his legacy.

Diverse tapestry of legal minds

Just as had occurred in 1910, when the first unified appellate court was created as part of the new country called “South Africa”, the background and experiences of the first eleven Concourt justices represented a remarkably rich and diverse tapestry of legal and political involvement.

This had two immediate consequences: most importantly, and led by President Nelson Mandela, the judgments of the Concourt were accepted unquestioningly by the executive and parliament, even when they went counter to the government’s own actions and decisions.

Secondly, the justices displayed a sophisticated and adept approach to the doctrine of the separation of powers, exercising due restraint at times, when the temptation must have been strong to intervene more emphatically when government had erred in law. Thus the Concourt soon established its legitimacy in the eyes of party politicians and the broader public alike.

The shaping of an erudite legal mind

With the passage of years, and given the fact that constitutional justices serve limited terms of office, it was inevitable and perhaps appropriate that those appointed to the Court should have less obviously strong “political struggle” credentials.

Moseneke’s retirement is especially significant for that reason. His entire career before appointment testifies to his intimate knowledge of and involvement in the fight against injustice before 1994. Most of the remaining justices have no such record. Given this reality, will the Concourt be able to maintain its pre-eminence as protector of the Constitution?

There can be few South Africans who experienced the brutality of the apartheid regime as early in life and for such a long period as Moseneke. That he emerged from such trauma to exhibit the degree of compassionate, principled and courageous leadership that has characterised his life is even more astonishing. In 1963 he was only 15 when he was convicted of anti-apartheid crimes, and sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment. He served this term on Robben Island. He was not idle, gaining his matric as well as two Bachelor’s degrees.

He completed his formal tertiary education through an LLB degree after his release. He served as an articled clerk at a Pretoria firm of attorneys from 1976. After admission as an attorney, he founded his own firm. He moved to the Bar in Pretoria from 1983, a brave move as he broke a pattern of racist exclusion in that institution.

With the unbanning of political organisations in 1990, he assumed high office in the Pan Africanist Congress. As such he played a central role in the drafting of the transitional Constitution of 1993. Thereafter he served as Deputy Chair of the Independent Electoral Commission which organised the first democratic elections in 1994. Later that year he acted for a short while as a judge, before immersing himself in business activities.

But, his commitment to the law as his first calling was renewed when he was appointed to the High Court in Pretoria in late 2001, followed a year later by his elevation to the ranks of the Concourt by President Thabo Mbeki. Less than three years later he was appointed deputy chief justice, in which office he served with distinction until retirement.

Proud legacy of eloquence and loyalty

Justice Moseneke delivered a number of very important judgments on behalf of the Concourt. Ironically, given the fact that, as deputy chief justice, he was passed over twice for appointment to the chief justiceship, he has frequently been associated with the notion of judicial deference in his interpretation of the separation of powers.

For instance, it was his judgment that finally put paid to the court challenges from those resisting the imposition of e-tolling in Gauteng. This was chiefly because he thought that such polycentric policy decisions belonged in the sphere of the executive, and were not decisions for a court of law.

On the other hand, his fearless commitment to constitutional principle is seen in his being part of the majority which upheld the appeal which set aside the establishment of the Hawks corruption-fighting agency as insufficiently independent. The judgment cited South Africa’s international treaty commitments to take steps to eliminate corruption.

Moseneke conducted himself throughout with enormous restraint, loyalty and courtesy notwithstanding his treatment by the executive. On the Bench, he was an eloquent and urbane participant in debates about the maintenance of the rule of law, democratic constitutionalism, and the transformation of society, in line with the values of the Constitution. He is the living embodiment of those ideals, tolerant and caring in all he does, and an inspiration to many.

This is best epitomised in the manner of his leaving office. As deputy chief justice, he had the unenviable task of chairing the Judicial Service Commission when it interviewed President Zuma’s nominee, Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, to be the chief justice. The tensions and animosity of that process were palpable. Yet when Moseneke spoke at the formal Concourt sitting to mark his retirement, he went out of his way emphatically to express his complete confidence in the chief justice, as follows:

I can say without any fear of contradiction that your integrity has been shown to be beyond question.

Such grace and magnanimity are rare in public life, so their impact is all the greater. South Africa and Africa need more leaders in the mould of Moseneke. He has just been in the news again, as one of the executors of Nelson Mandela’s estate. From their meeting on Robben Island over 50 years ago, the late president must have realised that here was a man of utter integrity. May the standards set by Dikgang Moseneke long continue to inspire good governance in South Africa.

By Hugh Corder, Professor of Public Law, University of Cape Town

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.