THINKING STRATEGICALLY ABOUT STRATEGIC MINERALS (Or: The “Justice” approach Africa needs to get ahead of the Just Energy Transition Curve)

Written by Hanri Mostert.

The old saying “if it cannot be grown, it must be mined” points an accusatory finger at our dependency on mineral resource extraction. No matter where in the world we are, our modern lifestyles bind us, inextricably, to this earth and all of its resources. Reversing a particular course of action – such as transitioning from fossil fuels to green energy – takes effort and requires adaptation. What does not change, though, is our utter dependence on the world’s mineral resources.

Our lifestyles, political choices, social activities and economic realities determine the minerals that are in high demand from time to time. For instance, magnesium, chromium and manganese – the minerals crucial to produce steel – are relevant during an economic growth spurt. Or a war. Rare earth minerals are essential to sustain the technological demands of our lives. And in the energy sector, minerals are needed too – even more so now than ever before – to keep the lights on. Be it uranium, coal – for so long South Africa’s hitherto biggest export product - or more recently lithium, cobalt and graphite, as greener options for energy generation and storage capacity become essential.

Mineral resource extraction defines Africa’s relationship with the rest of the world. Strategically important as a fuel and raw materials supplier, Africa also depends on such exports for its income and economic stability. This interdependent relationship is borne, at least partially, out of the history of colonisation, which placed Africa’s natural resources at the disposal of Europe’s industrial and productive sectors. The result was an asymmetrical relationship to which persisting disparities in wealth accumulation bear witness in contemporary trends.

Meanwhile, though, our world order has become increasingly multipolar and other powerful elements have gained a foothold in Africa. China has dominated the past decade as an African trading partner. There is even talk of “a shift of power from West to East”[1] as the interest of South Korea and Russia in African resources grow. Such developments bring both new potential and new risks to the African continent.

An AfDB paper recently emphasized that Africa has a key role in the global mineral value chains. When it comes to what the world now regards as minerals critical to the just energy transition, South Africa and Guinea hold more than one key resource and lie in the top ten of those minerals globally. The DRC, Zambia, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Ghana – among others - also find themselves among the top ten global producers of at least one key mineral each. Central and Southern Africa cater for more than four fifths of the world’s platinum and chromium. And 70% of the world’s need for cobalt – another mineral that is crucial to the just energy transition – comes from the DRC.

But within the value chains for minerals critical to the energy transition, Sub-Saharan Africa finds itself in a precarious position. Resource management in Zambia, DRC, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Angola, for instance, is generally characterized as weak. Environmental mismanagement, social risks, and poor governance have dire consequences, such as environmental degradation, livelihoods destruction, strained public health systems, marginalised communities, and inhumane working and living conditions.

Susan Nakanwagi, a recent PhD graduate of Dundee University, developed the notion of “criticality”, denoting the strategic importance of particular minerals for certain processes. Focusing specifically on minerals needed for the just energy transition, and their prevalence in Africa, her work exposes an interesting fact: Up to now, the industrialised economies of the mineral-consuming Global North countries have driven trends in the extraction of critical minerals. Their interests compel them to focus on the economic and industrial importance of such minerals, and the risk of supply shortages or breakdowns in some instances. They are less interested in the concerns pertinent to the developing countries of the Global South.

These concerns, Nakanwagi asserts, are varied and multiple, and relate to social, ecological, spatial, policy, political, technological and economic issues. Critical mineral-rich countries like the DRC and Zambia display the need to have further imperatives informing how these minerals are extracted and who should carry the costs and enjoy the benefits of such extraction. Such imperatives include:

- indigenous integration in the critical mineral value chain,

- the political landscape and existing resources, and

- the socio-cultural considerations of the surrounding communities of these critical mineral mining operations.

Nakanwagi shows that current criticality assessments do not consider these issues.

How can one place these concerns on the table where decisions about the extraction of minerals critical to the energy transition are made?

The work I did with Cheri-Leigh Young and Julie Hassman, and elsewhere also with Heleen van Niekerk, looking at the tenets of what we termed “extractive justice”, applies also to the context of the minerals-energy connection, and it can be useful in framing choices around how to pursue extraction of minerals that are critical to a new energy future. At MLiA, we’ve been working for years with the premise that Africa can benefit more fully from its mineral resources, and the rest of the world from its mineral and fuel investments in Africa, if there would be strong capacity to create and implement sound legal frameworks and good governance in the extractive sector. Investors need reliability of legal framework and governance practices to maximise profits. African governments need stronger capacity and expertise to negotiate equitable deals and enforce regulations in the extractives sector. We also believe that access to information and local expertise are powerful tools to address resource and power imbalances in the sector. These tools also enhance accountability and transparency; and they are significant enablers of more even bargaining positions.

Initiatives to guide policy development and investment choices in Africa’s extractive industries are necessary. They must promote the values underlying the desire for better governance practices, improved access to information and commitments to grow local expertise and narrow the knowledge gap. But what do these values really imply when it comes to the business and politics of extracting natural resources?

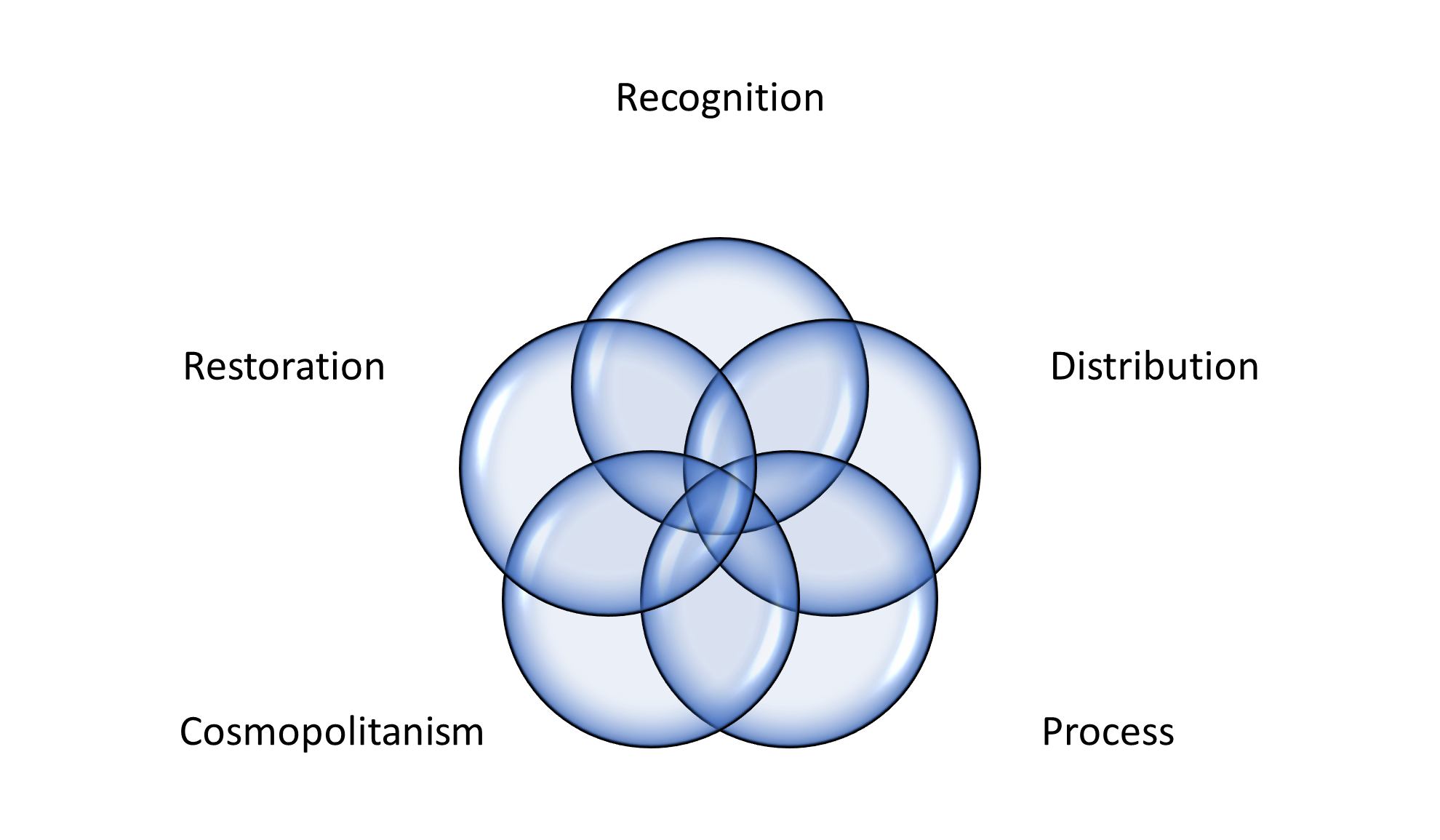

In our extractive justice work, we offered this thought: managing the inevitably complex, polycentric interests that accompany mineral extraction will be aided by a value-based approach informed by considerations of justice. We focused on three elements in our analysis:

For one, there must be “distributive justice” which entails rules ensuring benefit to those worse off in the system, and a system that ensures equal sharing of the costs and burdens of resource extraction. But levelling out socio-economic inequality is not enough. There must also be “recognition justice”: equitably distributing power and wealth requires recognition of affected groups’ culture, or way of life, their dignity as humans, and the inviolability of their physical integrity.

Further, Recognition and Distribution as conceived of above both need sound processes that drive decision-making. This is the “procedural justice” aspect. It is about the quality of treatment a person or a group can expect in their dealings with the state. Procedural justice thrives in conditions that foster impartiality, access to and fairness of decision making.

Building on this system, Nakanwagi goes two steps further, incorporating two more elements in the notion of extractive justice: She argues that a justice-based approach to resource management also demands “restorative justice”: implementing restorative practices to mitigate the negative consequences of mining, while providing economic incentives through secondary activities and more complex enterprises. She further includes the consideration of cross-border consequences and interests as crucial for resource management, explaining this to be “cosmopolitan justice”, a concept Elizabeth Bastida encourages for the extractive context specifically in her recently published book “The Law and Governance of Mining and Minerals: A Global Perspective.”

Based on the abovementioned system, there are at least five tenets to an ideal approach that will allow for the concerns of the global south, and particular Africa, to be kept in mind in negotiating the wheres, whats, hows and whos of extracting minerals critical to the energy transition. These tenets are what will make the energy transition “just”: distribution, recognition, process, restoration and cosmopolitanism.

1: Components of Extractive Justice

These tenets create Nakanwagi’s “holistic framework” in which to facilitate global sustainability and address climate change. They also give airtime to the challenges the developing world experiences because of extractivism.

Even though they do not explicitly mention it, regional and state-level policy frameworks, such as the African Mining Vision and the South African Mining Charter, already attempt to honour the notion of extractive justice, e.g. through their adherence to ‘social licence to operate’ and ‘participatory development’. Yet, community rights to consultation and/or free prior and informed consent (FPIC) remain ill-defined in, or absent from, enforceable legislation throughout the continent.

The task that lies ahead is to engage with Africa’s legislative frameworks, to envision how the five tenets of extractive justice can be included to protect the continent’s holding of strategic resources that are key to the imminent energy transition.

SOURCES:

African Union “African Mining Vision” (2009). Available at http://www.africaminingvision.org/amv_resources/AMV/Africa_Mining_Vision_English.pdf [accessed 9 Sept 2018]

African Union Commission, African Development Bank, and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa “Building a sustainable future for Africa’s extractive industry: From vision to action” (December 2011). Available at http://www.africaminingvision.org/amv_resources/AMV/AMV_Action_Plan_dec-2011.pdf [accessed 9 Sept 2018].

Anderson, J. (tr) The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflict (1996) x.

Bastida, Ana Elizabeth, The Law and Governance of Mining and Minerals: A Global Perspective (Hart Publishing 2020), ISBN 9781849463454 (hardback), published as Volume 3 of the series Global Energy Policy (P Cameron, P Bekker and V Roeben, series editors).

Mostert, Hanri, and Heleen van Niekerk, 'Disadvantage, Fairness, and Power Crises in Africa: A Focused Look at Energy Justice' in Yinka Omorogbe, and Ada Ordor (eds), Ending Africa's Energy Deficit and the Law: Achieving Sustainable Energy for All in Africa (Oxford, 2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 19 Apr. 2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198819837.003.0004, accessed 27 Jan. 2023.

Mostert, Hanri, Young, Cheri-Leigh & Hassman, Julie L (2019) ‘Towards extractive justice: Europe, Africa and the pressures of resource dependency’, South African Journal of International Affairs, 26:2, 233-250, DOI: 10.1080/10220461.2019.1608853

Nakanwagi, Susan ‘Just criticality: a justice framework for critical minerals value chains’ PhD University of Dundee 2022

Rombouts, SJ (2014) ‘Having a say: Indigenous peoples, international law and free, prior and informed consent’ [Doctoral Thesis, Tilburg University]. Wolf Legal Publishers (WLP)

Summers, RS ‘Evaluating and improving legal processes-a plea for “process values”’ (November 1974) 60 Cornell Law Review 1; LB Solum ‘Procedural justice’ (November 2004) 78 Southern California Law Review 181.

Summers, RS ‘How Law Is Formal and Why It Matters’ (July 1997) 82 Cornell Law Review, article 11, 1166

Vittorini, Simona and Harris, David ‘New topographies of power? Africa negotiating an emerging multipolar world’ in Ton Dietz et al. (eds), African Engagements: Africa Negotiating an Emerging Multipolar World (Leiden: Brill, 2011) 283-284.

Mangala, Jack (ed.), Africa and the European Union: A Strategic Partnership (Palgrave Macmillan 2013);

Adu Boahen, A African Perspectives on European Colonialism (2nd edn, John Hopkins University Press 2011);

Jing, Men and Barton, Benjamin (eds), China and the European Union in Africa: Partners or Competitors (1st edn, Ashgate 2011) 6;

Rodney, Walter How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Pambazuka Press and CODESRIA, 2012).

Chitonge, Horman Economic Growth and Development in Africa: Understanding Trends and Prospects (Routledge, 2015) 203.

Swiegers, Wotan The New Scramble for Africa, on BBC Radio 12 April 2009, quoted in Simona Vittorini and David Harris, ‘New topographies of power? Africa negotiating an emerging multipolar world’ in Ton Dietz et al. (eds), African Engagements: Africa Negotiating an Emerging Multipolar World (Leiden: Brill, 2011) 293-294.

[1] Wotan Swiegers, The New Scramble for Africa, on BBC Radio 12 April 2009, quoted in Simona Vittorini and David Harris, ‘New topographies of power? Africa negotiating an emerging multipolar world’ in Ton Dietz et al. (eds), African Engagements: Africa Negotiating an Emerging Multipolar World (Leiden: Brill, 2011) 293-294.