Discussing Reversion Rights at the CC Global Summit 2020: the history of South Africa's provisions

Reversion rights exist in many forms around the globe and were discussed in some sessions of the Creative Commons Global Summit 2020. One of these sessions was entitled 'How reversion rights can fix copyright: reclaiming lost culture and getting authors paid'. On this panel, I joined A/Prof Rebecca Giblin (Melbourne University and Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia (IPRIA)), Dr Ula Furgal (CREATe Centre, University of Glasgow), Josh Yuvaraj (Faculty of Law, Monash University, Melbourne, and a Visiting Scholar at the University of Melbourne) and Brianna Schofield (Authors Alliance, US). For more about the panelists and their presentations, read Josh's post - Creative Commons Global Summit 2020 – Abstracts and Bios

The purpose of the panel, as eloquently stated by Prof Giblin, was to show that discussions do not need to be binary or pit stakeholder interests against each other. Instead these rights can be harnessed so that creators can fairly paid and culture can be preserved and accessed. 'Reversion rights provide a way of doing both at the same time. If cultural institutions and the broader public joined forces with creator groups to secure more ambitious rights than the limited ones that currently exist, we have the opportunity to create new income streams for creators and better access for all'.

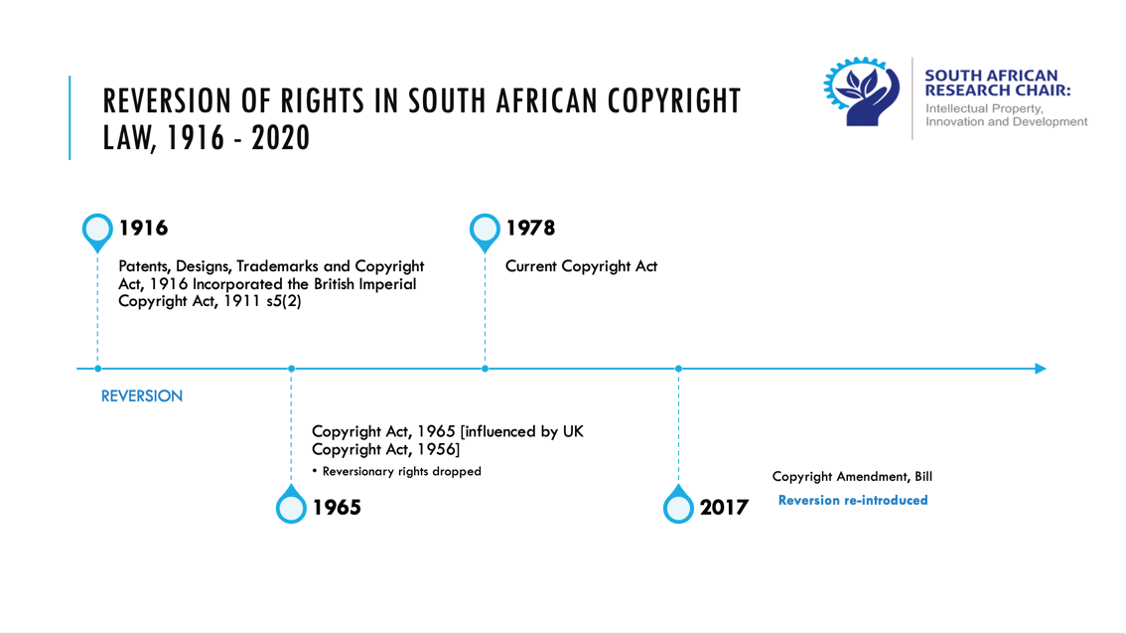

The other panelists discussed reversionary rights in the EU, the US and Australia. Josh shared results from their recent empirical study on reversion clauses in Australian publishing contracts. In my contribution to the panel, I sketched the history of reversion rights in South Africa starting with the Patents, Designs, Trademarks and Copyright Act, 1916 which incorporated the British Imperial Copyright Act, 1911 s5(2), through their omission from the 1965 Copyright Act (following the 1956 changes in British copyright law, to the Copyright Review Commission (2011)'s recommendation that automatic reversion be enacted in South African copyright law to the current provision in the Copyright Amendment Bill. My slides are available here.

The 1916 provision read as follows:

'Provided that, where the author of a work is the first owner of the copyright therein, no assignment of the copyright, and no grant of any interest therein, made by him (otherwise than by will) after the passing of this Act, shall be operative to vest in the assignee or grantee any rights with respect to the copyright in the work beyond the expiration of twenty-five years from the death of the author, and the reversionary interest in the copyright expectant on the termination of that period shall, on the death of the author, notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary, devolve on his legal personal representatives as part of his estate, and any agreement entered into by him as to the disposition of such reversionary interest shall be null and void, but nothing in this proviso shall be construed as applying to the assignment of the copyright in a collective work or a licence to publish a work or part of a work as part of a collective work.'

The successful use of the 1916 reversionary provisions in the settled Linda and Disney case was also discussed. For a full overview of that case and the use of this clause see Prof Owen Dean ‘Awakening the Lion in the Jungle - The story of the Lion Sleeps Tonight Case’ 31/05/2019. The clause was not tested in court because of the settlement but it would be fair to say that the parties' views on the strength of the case being made on behalf of Linda's deceased estate had an impact on the decision to settle and the amount of the settlement.

The reversionary provision was not included in the 1965 and 1978 Copyright Acts and in 2011, the CRC made the following pronouncements and recommendations:

- “The CRC believes that the Copyright Act must be amended to provide for the reversion of assigned rights to royalties 25 years after the assignment of such rights. Such an amendment will help relieve the plight of composers whose works still earn large sums of money, which are going to the assignees of the composers’ rights long after the assignees (or their predecessors) have recouped their initial investment and made substantial profits, in excess of those anticipated when the original assignment was taken.” para xx, page 5

- “In South Africa, there is a high proportion of musicians and authors who are ignorant about copyright issues and, as a result, there are several cases where the rights are assigned to third parties without a full understanding of the implications. In order to minimise the impact of these transactions, the CRC has recommended an automatic reversion of copyright to the original owner after 25 years, regardless of the terms of the original transactions.” para 14.1.15, page 100

- “The Copyright Act must be amended to include a section modelled on that in the US Copyright Act providing for the reversion of assigned rights 25 years after the copyright came into existence. (The drafters of the section must have regard for proposals currently under discussion in the US for an amendment of the section to overcome difficulties encountered in practice.) Such an amendment will go far to relieve the plight of composers whose works still earn large sums of money that are going to the assignees of the composers’ rights long after the assignees (or their predecessors) have recouped their initial investment and made substantial profits, in excess of those anticipated when the original assignment was taken. The period proposed is shorter, based on the fact that the local copyright duration is shorter than the American one” para 15.1.9, page 102

- "SAMRO should take active steps to identify those persons entitled to the reversion of copyright under Section 5 of the Third Schedule to the 1916 Act (i.e. in respect of works composed before 11 September 1965 by composers who died less than 50 years ago and more than 25 years ago) and see to it that any royalties due to them are paid. During the hearings it was ascertained that no attempts are made to collect royalties falling in this category, despite the success enjoyed by Prof. Owen Dean in collecting royalties for the heirs of Solomon Linda.” para 15.2.7, page 105

Following these recommendations, the Copyright Amendment Bill B13B-2017, clause 23 provides the following amendment section 22:

‘‘(3) No assignment of copyright and no exclusive licence to do an act which is subject to copyright in such work shall have effect unless it is in writing and signed by or on behalf of the assignor, the [licenser] licensor or, in the case of an exclusive [sublicence] sub-licence, the exclusive [sublicenser, as the case may be] sub-licensor, as stipulated in Schedule 2: Provided that assignment of copyright in a literary or musical work shall only be valid for a period of up to 25 years from the date of such assignment.

This clause is not the same as the US provision (17 U.S. Code §â¯203.Termination of transfers and licenses granted by the author) and its merits have been much debated. The purpose of the panel was to provide comparators from other jurisdictions and to present empirical evidence of experiences in other jurisdictions on the use of similar clauses.